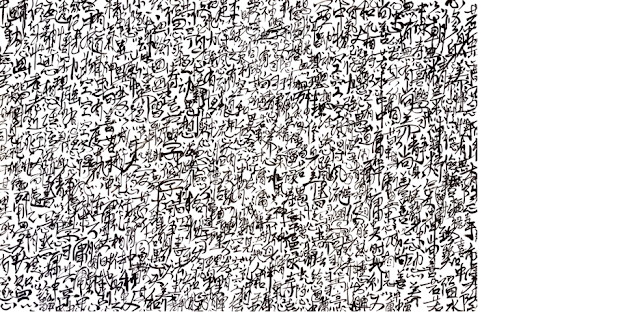

The Wasteland of pictogram

|

| Wasteland. (2019) |

A Sea of Fragments

At first glance, the work appears overwhelming: an endless field of characters, each stroke alive, each word pressed into the surface like waves upon waves of an ink ocean. It is a wall of text, yet it refuses to be read as a single, linear narrative. Instead, it must be wandered, like a forest of words, where each step offers a new vista.

The artist builds the composition out of fragments. Words and phrases drawn from Daoist, Buddhist, and Confucian traditions are scattered like driftwood across the sea of paper. Each fragment is a floating vessel — “空” (emptiness), “道” (the Way), “中” (the middle), “心” (heart-mind). Some shine brightly, bold in their brush; others recede into near-illegibility. Together they form not coherence but multiplicity — a mirror of life itself, where experience does not unfold in a single story but in shards, roles, and overlapping identities.

There is beauty in this fragmentation. The piece is an encrypted field: its meanings resist easy decoding, but in that resistance lies its vitality. For the casual glance, it is chaos; for the attentive gaze, it becomes a cosmos of interwoven traditions. The repetition of certain words — “空, 空, 空” — becomes mantra-like, echoing Buddhist teaching that true emptiness is full of paradox: the word itself cannot be empty, and yet it gestures toward the unspeakable.

Confucian balance, Daoist simplicity, Buddhist release — all are here, but not as neat doctrines. They collide, overlap, and blur, echoing Lin Yutang’s insight that the Chinese psyche is always tripartite, always living within multiple frameworks at once. This work does not resolve them; it lets them coexist, in tension and in dialogue.

The visual density recalls Jackson Pollock’s drip paintings, where the eye cannot settle but must roam. Here, instead of paint splatters, we encounter fragments of language, a dictionary shattered and spilled. Each viewer reads differently, each decoding guided by their own experience, their own inner lexicon. The artwork becomes a mirror, reflecting the interpreter as much as the artist.

To stand before it is to be asked not to read but to drift — to sip wine, to let the mind meander, to allow meaning to rise and sink like flotsam. Interpretation becomes less a task than a journey, a form of meditation. In its chaos, the work affirms the dynamism of existence: that we are fathers, sons, lovers, seekers, all at once; that the fragments of our roles and philosophies do not betray incoherence but speak of the vast complexity of being.

Like T.S. Eliot’s The Waste Land, the piece revels in shards — “these fragments I have shored against my ruins.” Yet unlike Eliot’s despair, here the fragments pulse with vitality. They invite not mourning but play, not disillusionment but curiosity.

In the end, the artwork is not a riddle to be solved but a process to be entered. It is both the artist’s creation and the viewer’s participation, a co-authored field of meaning. To look is to think; to think is to reflect; to reflect is to become. In its density, the piece becomes not a burden but a liberation: a reminder that life, like language, need not resolve into one story. It can remain a sea of fragments — infinite, shifting, alive.

确实,这个作品依托于碎片化词语的广阔画面,从道教、佛教和儒家的丰富织物中取词,洒在广阔的木材碎片海洋之上。每个词,就像这大词海中的一片漂流木,都包含着深奥智慧的隐藏内核,回应了中国文本的加密性质。加密的美丽在于其复杂性和解释的双重性;一方面,它是一个难以解码的挑战,另一方面,对于那些敢于深入其深处的人,它揭示了一个意义的世界。

例如,考虑"空","空","空"这三个词,它们象征着佛教的哲学。连用这些词语暗示了通过剥去世俗欲望的层层来到达完全空虚的状态的过程。这个过程类似于佛教通过放弃身心的依恋来达到觉悟的状态的做法。"空"这个词本身就是悖论,因为在它被提及的时候,它表明了一些东西,而那个东西本质上并不是空的。因此,人们可能会说"空"这个词充满了意义,这种微妙只有在深入反思后才能理解。

这件作品也回应了儒家的教诲,体现在"中道"的概念中。中道深深地植根于儒家哲学,促进生活各个方面的平衡和和谐。相比之下,道家的教义主张简单和极简,渴望削减所有世俗的物质,以实现与自然世界的一体化。这种做法让人想起物理还原主义,其中鼓励人们用最少的东西来维持自己的生活,从最简单的事物中找到乐趣。

然而,人们必须注意的是,生活,通过这件作品的感知,看起来是碎片化的,而不是连贯的。在生活的各个阶段,我们扮演着不同的角色--作为一个父亲,一个儿子,一个情人,等等。这些角色,尽管是不同的,但不一定暗示着不一致;相反,他们强调了人类存在的动态性。

中国学者林语堂提出,在每个中国人的心中,都存在三个哲学框架--儒家、道家和佛家。每个框架都有一个独特的目的;儒家指导国家的治理,道家告诉艺术努力,从社会约束中释放个体,推动自我的无形表达,而佛家则帮助导航人际关系,促进友情和相互尊重。

虽然艺术品看起来是碎片化的,但它具有固有的整体性。每一件作品,虽然是自身的实体,但都与其他作品存在关系,创造了一种微妙的平衡,就像杰克逊·波洛克的画作中的笔触。这些"浮动"的词语,就像一个碎片化的字典,封装了无数的想法,激发了观众的好奇心,促使他们解开潜在的意义。

这样的作品邀请观众积极参与。在品尝一杯红酒的时候,他们被鼓励让他们的思想漫游,思考,解读交织在作品中的无数含义。这不仅仅是努力理解,而是让心灵踏上一次智力冒险,找到混乱中的意义,就像费尼克斯从灰烬中崛起,就像T.S.艾略特在他的诗"荒原"中所建议的那样。

本质上,艺术品是启动内省和理解的媒介。它不仅仅是艺术家的创作,也是观众的解读,每个人都带着他们自己的视角来看待作品,理解混乱,发现碎片化的意义。

Comments

Post a Comment