Writing as Cosmos

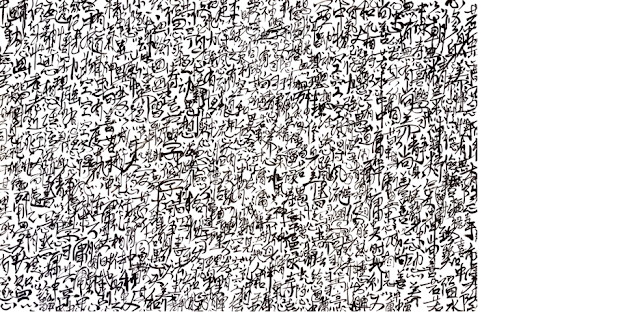

Cosmo. (2019) Chinese Ink on Rice Paper. Size: 140cm x 70cm,

Writing as Cosmos — Dense Calligraphy and the Philosophy of Virtue

Introduction: Calligraphy as Living Text

Unlike the spacious and measured semi-cursive of Chang’an Autumn View, this piece overwhelms the eye with a dense field of ink. Characters swarm and overlap, layered so tightly that legibility yields to rhythm, creating a visual cosmos of script. At first glance it appears almost abstract, yet within the texture emerge words and phrases:

“德儉格物致知,福禄寿喜,学习静以养心,动以养身,爱其所同,敬其所异,以诚相见,以礼相待……”

The phrases evoke a moral-ethical universe: Confucian cultivation (格物致知), Daoist moderation (尚善若水), and Buddhist-like serenity (静以养心). They are woven into the visual surface so that reading becomes meditation, and seeing becomes reading.

1. The Visual Structure

-

Density: Unlike the measured balance of traditional calligraphy, here text forms a wall of ink, eliminating conventional margins. This recalls the monumental sutra transcriptions of Buddhist monks, where repetition itself becomes devotion.

-

Directionality: Although characters are still vertically aligned, their clustering breaks the flow — forcing the reader to wander, pause, lose and rediscover meaning. This mimics the wandering of the mind in philosophical reflection.

-

Texture: Variations in thickness, speed, and overlap create a weaving effect, as if each stroke were a thread in a cosmic tapestry.

2. Philosophical Content in the Text

The embedded words form a constellation of virtues, values, and aspirations:

-

Moral Virtues: 德 (virtue), 儉 (frugality), 诚 (sincerity), 礼 (ritual respect).

-

Cultivation of Self: 静以养心 (nurture the heart with stillness), 动以养身 (nurture the body with movement), 不停学习 (unceasing study).

-

Harmony: 天时地利人和 (timing, place, and human harmony), 爱其所同敬其所异 (love commonality, respect difference).

-

Wisdom and Daoist Paradox: 大智若愚 (great wisdom appears as folly), 小隐于山,大隐于朝 (the recluse in mountains, the greater recluse within court).

-

Existential Reflection: 空中有物,空空空 (in emptiness there is being; emptiness upon emptiness).

The text becomes a mosaic of Chinese wisdom traditions — Confucian ethics, Daoist paradox, Buddhist emptiness — brought into a living, handwritten texture.

3. Brushwork and Emotional Quality

-

Gestural Energy: Each character is alive, some angular, some rounded, some dissolving. This reflects the infinite variation of human thought.

-

Controlled Chaos: While dense and seemingly chaotic, the piece maintains coherence — strokes never fully collapse. It is a disciplined chaos, mirroring the Daoist truth that order and disorder are interdependent.

-

Breath Rhythm: The ink density suggests cycles of deep concentration and release, like breathing meditation (调息).

4. Tradition and Modern Resonance

-

Chinese Lineage: This recalls the work of Zhang Xu (张旭) and Huai Su (怀素) in the Tang dynasty, masters of wild cursive (狂草), where legibility gives way to pure expression. It also evokes scriptural copying traditions, where writing becomes ritual.

-

Western Resonance: To a Western eye, this parallels Jackson Pollock’s drip paintings or Cy Twombly’s script-like scrawls. Text ceases to be mere signification and becomes visual rhythm. Yet unlike Pollock, this is not non-referential — each word still carries moral-philosophical weight.

5. Interpretation: A Sea of Words, A Sea of Mind

This piece represents not a single poem, but a universe of thought. The density reflects the impossibility of isolating wisdom; it is always interwoven, one virtue leading to another.

Reading becomes an act of immersion. One does not decode line by line, but enters a sea of words — surfacing occasionally on familiar phrases, then sinking again into visual flow. This mimics the practice of self-cultivation: sometimes clear, sometimes obscure, always continuous.

Conclusion: The Calligraphy as Cosmos

In this dense calligraphy, the brush no longer merely records words — it creates a cosmos of thought and being. Every stroke embodies a fragment of philosophy, yet together they form a living texture that transcends linear reading.

Here, writing becomes meditation, ink becomes philosophy, and calligraphy becomes both scripture and abstraction. It is at once Chinese in its foundation — Confucian, Daoist, Buddhist — and modern in its aesthetic, resonating with global traditions of abstract art.

Through this, the viewer is invited not only to read, but to contemplate: to find stillness in density, wisdom in paradox, and beauty in the flowing chaos of the written line.

Dense Calligraphy — The Ink as Psyche

1. The Compulsion to Write: Freud and Repetition

Freud described the repetition compulsion as the psyche’s way of working through unresolved tension — repeating gestures not to communicate something new, but to process an inner necessity.

-

In this dense calligraphy, the artist does not stop at legibility. Characters multiply and overrun margins, as though writing itself is more important than what is written.

-

This echoes Freud’s notion: repetition is not about communication, but about mastery — the psyche compulsively writing its own order into chaos.

Thus, the sea of ink is not merely “philosophy expressed,” but also a working-through of psychic necessity.

2. The Field of Ink as Unconscious

Lacan would see in this density the Real breaking through the Symbolic.

-

Chinese characters, as carriers of cultural meaning, belong to the Symbolic order. They represent order, ethics, tradition.

-

But when multiplied into illegibility, they collapse into texture. At this point, meaning dissolves — the Real emerges, that which cannot be symbolized.

So the calligraphy becomes a stage where the Symbolic (virtue, philosophy) collapses into the Real (chaotic ink, unconscious drive).

Reading it is like approaching a dream: you glimpse fragments (virtue, emptiness, sincerity), but always through the mist of excess.

3. Jung: The Calligraphy as Mandala

Jung often spoke of the mandala as a symbol of psychic totality — circular, dense, patterned, overwhelming.

-

This calligraphy, though not circular, functions as a linguistic mandala.

-

The dense clustering is not just decoration; it is a psychic attempt at wholeness. Every word, every virtue, every paradox must be included. Nothing left out.

Here the artist shows the Jungian impulse toward individuation: to inscribe the total psyche, holding contradictions together (order/disorder, virtue/emptiness, clarity/obscurity).

4. Winnicott: Ink as Transitional Space

Winnicott spoke of art as a transitional space — a realm between inner psychic reality and outer shared reality.

-

This work is both deeply personal (a compulsive flood of strokes) and culturally shared (words that belong to Confucian, Daoist, Buddhist traditions).

-

In this sense, the inked page is a Winnicottian “play space” where the artist negotiates between inner compulsion and cultural inheritance.

Thus, the density is not chaos for its own sake — it is play, a testing ground for meaning, much like a child endlessly scribbling to master presence in the world.

5. Existential Drive: The Anxiety of Emptiness

At a deeper level, the density may reflect an existential anxiety: the fear of void, of silence, of blank space.

-

In Daoism and Zen, emptiness (空) is liberation.

-

But for the psyche, emptiness is also threat — annihilation, nothingness.

By covering the page with strokes, the artist wards off emptiness. Every gap is filled. Every silence is drowned in ink. It is both affirmation and defense: a way to inscribe being against the pull of nothingness.

This echoes Sartre: existence is a nausea before the void, and art is a gesture to make the void bearable.

6. The Artist’s Possible Intention (or Drive)

-

Philosophically, the artist intends to weave Confucian, Daoist, Buddhist traditions into one tapestry.

-

Psychically, the artist enacts:

-

A Freudian repetition compulsion (writing as endless working-through).

-

A Lacanian eruption of the Real (meaning dissolving into ink).

-

A Jungian mandala-making (totalizing, holding opposites).

-

A Winnicottian play (negotiating between inner psyche and outer culture).

-

An existential defense against emptiness (filling the void with being).

-

Conclusion: The Artist’s Psyche in Ink

This dense calligraphy is both cosmos and symptom.

-

As cosmos, it presents a world of virtue, philosophy, and wisdom.

-

As symptom, it reveals the psychic necessity to write endlessly, to fill, to weave, to resist void.

Thus, the artwork lives in paradox: it is both a meditation and a neurosis, both cosmic scripture and personal compulsion.

And perhaps that is why it resonates so powerfully: because all of us, in different ways, struggle between the desire for clarity and the compulsion for excess, between the silence of emptiness and the flood of words.

Comments

Post a Comment